February 26, 2026

Thursday links, AI and immigration

- Chris Arnade: What Holds America Together?

The best description of the conundrum America is in and the future of the American dream I have seen, accounting for the difference between “thin” (superficial) and “thick” culture. Good bit about immigration too:

Our tolerance for thin differences is also why immigration works better here than in other countries. That is especially true of front-row immigrants (highly educated), since they are leaving cultures they didn’t fit into at a thick level (entrepreneurial). They have self selected for being a natural American, at a thick level.

My own thoughts about and experience with immigration and the American dream match the above.

- Jessica Hullman: Living the metascience dream (or nightmare) with AI for science.

AI begets AI, as previously noted. Papers will be “safer”. Nuance will be lost. The comments to the post are just as enlightening.

- Paris Marx: Sam Altman’s anti-human worldview.

No nuance here either. Altman is so unabashedly anti-human that any of his public appearances are right out of a CS Lewis essay or story.

- Terry Godier: Current.

A new RSS reader ↬John Gruber which I am yet to check out. I do like the idea behind it, which tries to tame Dave Winer’s river of news a full two decades after he described the concept. I am less enthusiastic about the website copy: there is so much of it, and it is written in just such a way that it smells strongly of LLM assistance. I don’t think I mind it that much — though my skin still crawls when I see a “not this but that” phrase — and will chalk it up to the font-overload era of 1990s computing when we were just figuring out how to use the many typefaces available.

February 25, 2026

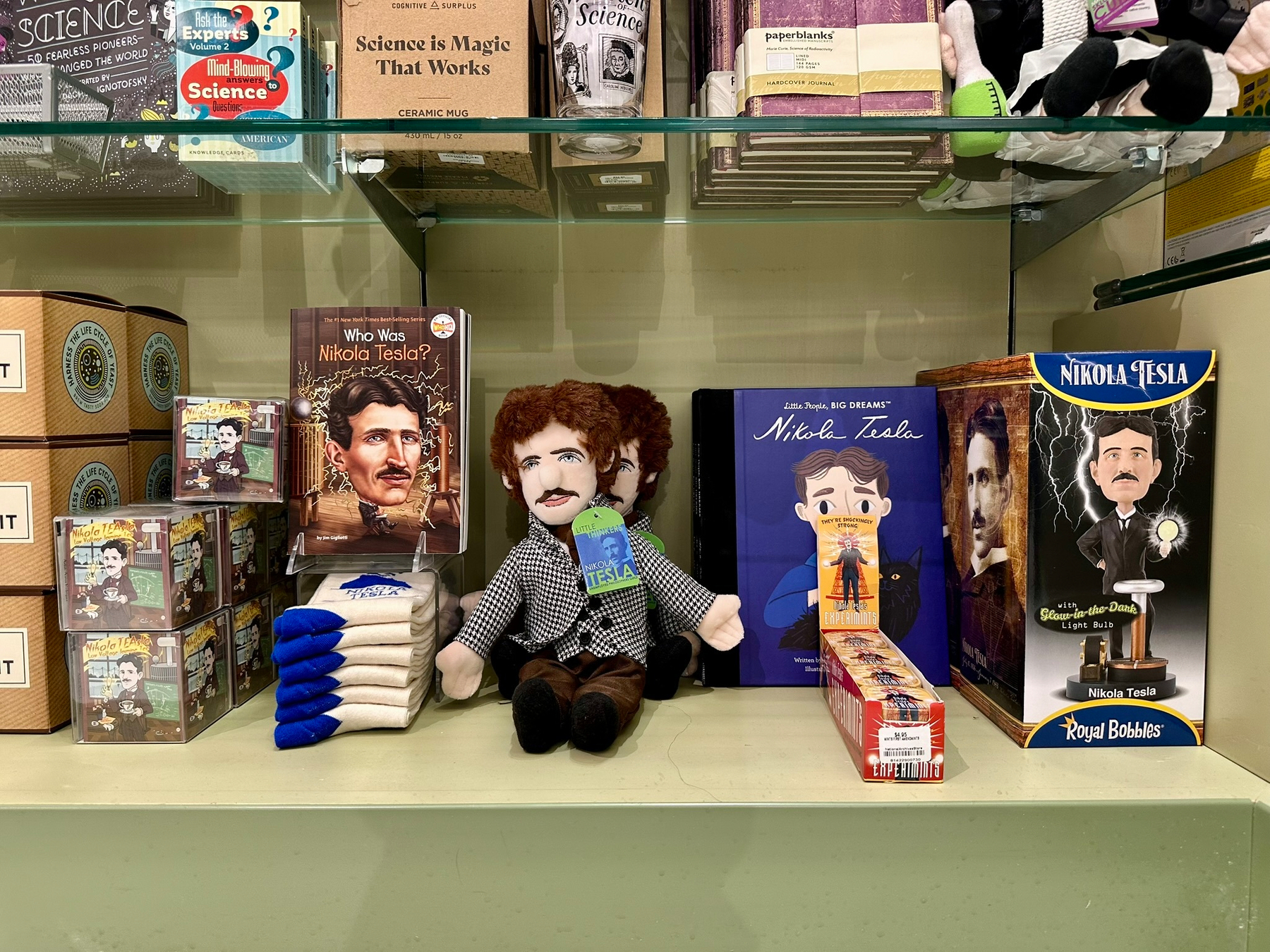

It warms my heart that Nikola Tesla has a whole shelf for himself at the National Archives gift shop. Thomas Edison? Nowhere in sight. It seems like only yesterday that Matthew Inman felt the need to publish a whole screed on why Tesla was the alpha geek but no, it was 2012, and his campaign bore fruit.