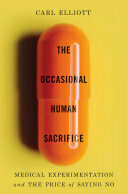

📚 Finished reading: The Occasional Human Sacrifice by Carl Elliott

The Occasional Human Sacrifice puts faces, personalities, anxieties and neuroses to the names of people who acted as whistleblowers to some of the biggest ethical failures in clinical trials. Some are textbook, like Tuskegee or the Willowbrook hepatitis studies, but many were either new to me, or just barely registered when they were briefly covered.

Elliott was himself a whistleblower in the case of Dan Markingson so he is hardly impartial to their cause — caveat lector — but the cases presented seem truly egregious. And not all of them are ancient history: Paolo Machiarrini experimented on humans without oversight as recently as 2014.

The picture you get is bleak and does not fill one with confidence about clinical research anywhere in the world. Physician-scientists are careless at best, selfish profiteers at worst, people who sit on ethics committees are a bunch of box-checkers, institutions are insular and protective of their own. Of course, there is major selection bias going on: yes, institutions protect their own but then there are many of their members who are accused daily of misconduct by conspiracy theorists, biopharma lobbyists, and the occasional psychopath. Some IRBs are indeed approval mills, but then there are those which truly protect research subjects, though alas what they do doesn’t make it into a book. How to tell where the equilibrium should lie?

In fairness to the book, it does not pretend to be a grand unifying theory of what is wrong with medical research. It is a collection of vignettes, no more and no less, and as such is an important source of “real-world” information to the research community. It is also a big honking red flag to any person thinking to blow the whistle on wrongdoings medical or not: it is a difficult path to take, with no vindication at the end.

Is lithium deficiency an important factor in developing Alzheimer’s disease? A recent paper in Nature provides some convincing evidence, mostly from mice. For example:

Replacement therapy with lithium orotate, which is a Li salt with reduced amyloid binding, prevents pathological changes and memory loss in AD mouse models and ageing wild-type mice.

I know quite a few doctors who would say lithium (carbonate) deficiency is responsible for many behavioral issues in adults, but this is not what they had in mind! (↬Derek Lowe)

Well that was fast:

“At the FDA’s request, Dr. Vinay Prasad is resuming leadership of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research,” HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon said. “Neither the White House nor HHS will allow the fake news media to distract from the critical work the FDA is carrying out under the Trump administration.”

Maybe lobbying isn’t as effective as I thought? I am sure there are stories to be told about what happened during these two weeks.

Making lobbying great again

Here are a few good comments on what recently happened at the FDA:

- Washington Post: What the ouster of a top FDA regulator shows about Trump world divisions

- The Atlantic: The Man Who Was Too MAHA for the Trump Administration

- Science: Vinay Prasad: That Was Fast

V(inay) P(rasad)’s ouster was clearly death by lobbyists, but then they had plenty of fodder. The current administration does seem to be going for a mid-to-late 19th century vibe in many ways, and this is one of them. Sure, Ulysses Grant probably didn’t coin the word, but isn’t that the peak period when those who had the president’s ear could get things done quickly and blatantly? Whether that excites you or scares you, well, that depends on what kind of person you are and what you do for a living.

Selfishly speaking, it will be good to see VP back publishing oncology papers. Here is a recent one about informative censoring in clinical trials, with a lay summary here. More of that, please.

A few choice excerpts from a NYT investigation, Medicare Bleeds Billions on Pricey Bandages, and Doctors Get a Cut:

For one patient in Nevada, Medicare spent $14 million on skin substitutes over the course of a year, according to billing records reviewed by The Times. The wound of a patient in Washington State persisted after Medicare paid $6 million for the coverings. A man in Texas got $1.3 million of bandages despite having no wound at all.

Five years ago, the most expensive skin substitute cost $1,042 per square inch, while some were as cheap as $45. Today, the three most expensive products on the market each cost more than $21,000. (Samaritan Biologics, a company in Memphis that sells the three products, did not answer questions about why they cost so much.)

For the first six months of a new bandage product’s life, Medicare will set the reimbursement rate at whatever price a company chooses. After that, the agency adjusts the reimbursement to reflect the actual price paid by doctors after any discounts.

To circumvent the reimbursement drop, some companies simply roll out new products.

The doctor who earned the most for skin substitutes last year was Dr. Aaron Jeng of Southern California, according to Early Read’s analysis. Medicare paid him $117 million. (Dr. Jeng declined to comment.)

Another high earner, Dr. Stephen Dubin of Las Vegas, was paid $17 million by Medicare for skin substitutes in 2024. (He estimated that after expenses, he took home roughly $4 million.) Dr. Dubin retired at the end of last year, in part, he said, because of increased competition for wound patients. Sometimes he would show up at a patient’s home only to find that someone from a different clinic had placed a new skin substitute the day before.

The article is 3 months old but still relevant: a day after it came out the administration announced that it was indeed delaying implementation of the new reimbursement rules until 2026. Wouldn’t it be neat if there were a government department that deals with this kind of fraud, waste and abuse?

Microsoft claims their new medical tool is “four times more successful than human doctors at diagnosing complex ailments”. Unsurprisingly, what they meant by “diagnosing a disease” was the thinking-hard part, not the inputs part:

To test its capabilities, “MAI-DxO” was fed 304 studies from the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) that describe how some of the most complicated cases were solved by doctors.

This allowed researchers to test if the programme could figure out the correct diagnosis and relay its decision-making process, using a new technique called “chain of debate”, which makes AI reasoning models give a step-by-step account of how they solve problems.

If and when deployed, how likely is it that these algorithms will get a query comparable to a New England Journal of Medicine case study? Most doctors don’t reach those levels of perception and synthesis, let alone the general public.

I will have more to write about this soon (ha!), but until the stars align for an extended writing session here is a good opinion piece from FT’s John Thornhill about why LLMs may not be all that great for lay people dabbling in, for example, medicine:

When the test scenarios were entered directly into the AI models, the chatbots correctly identified the conditions in 94.9 per cent of cases. However, the participants did far worse: they provided incomplete information and the chatbots often misinterpreted their prompts, resulting in the success rate dropping to just 34.5 per cent. The technological capabilities of these models did not change but the human inputs did, leading to very different outputs.

The emphasis is mine, because it is a neat summarization of what I wrote 2 years ago. Humans are unique not because of what’s inside our heads but because of how we interact with the environment. There will be no artificial general intelligence until that problem is solved.

Once a decade, I am obligated to read a book from Eric Topol. Ten years ago it was during a rotation at Georgetown where they were handing around copies of The Creative Destruction of Medicine like candy. Of course, if those books had truly been candy they would have been of the sort that quickly congeals into an inedible hard lump because nothing in The Creative Destruction… aged well.

Well this year Topol has a book out on aging, and if it weren’t for some high-profile endorsments I would not be paying it two cents. But then I saw Nassim Taleb praising its rigor and scholarliness, highlighting as an example that Topol cites multiple trials for each claim. One can hope the trials he cites actually back up the claims, and to confirm that is indeed the case I now have Super Agers on the pile. Kindle version only: physical space in our library is too precious for Topol.

Noah Smith writes about health care costs:

So overall, health care is probably now more affordable for the average American than it was in 2000 — in fact, it’s now about as affordable as it was in the early 1980s. That doesn’t mean that every type of care is more affordable, of course. But the narrative that U.S. health costs just go up and up relentlessly hasn’t reflected reality for a while now.

And he has the data to back it up, though some of it feels like playing the denominator whack-a-mole. Interesting regardless. (ᔥTyler Cowen)

Yes, investigator-initiated clinical trials take time. But rather than back-patting and boasting about how it can still be done despite the setbacks, why not propose solutions for how to speed them up? I made a few off-the-cuff suggestions but you can also find serious efforts on that front.