From our visit to the US Capitol: a Corn-inthian column decorating the old entrance.

🎙 If you have two hours to spare (a particularly long commute, perhaps?) you could do worse than listen to the most recent episode of the Doomscroll podcast with guest David Wengrow, co-author of The Dawn of Everything. Pairs well with Planet of the Barbarians!

From our visit to the US Capitol: a Corn-inthian column decorating the old entrance.

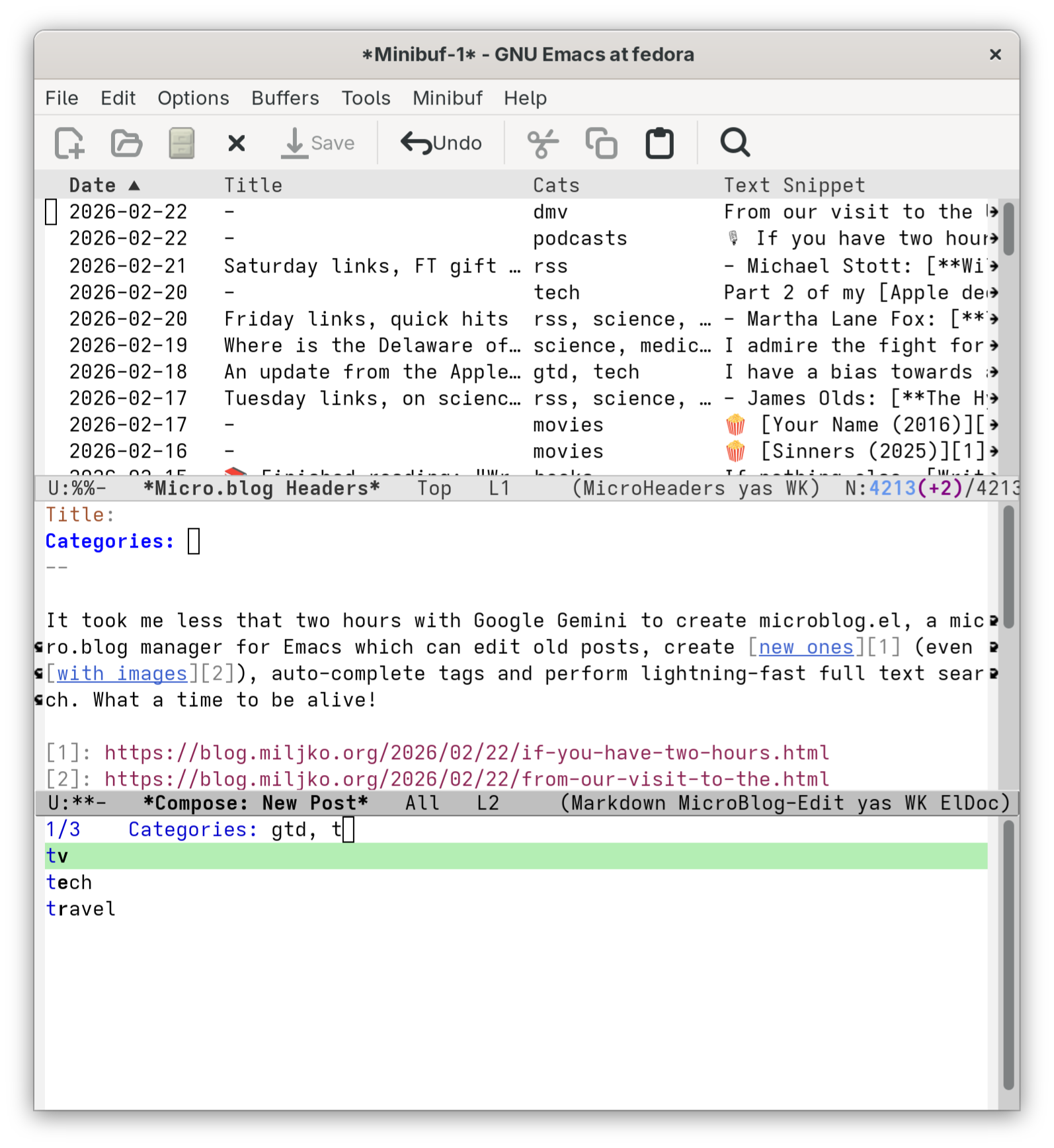

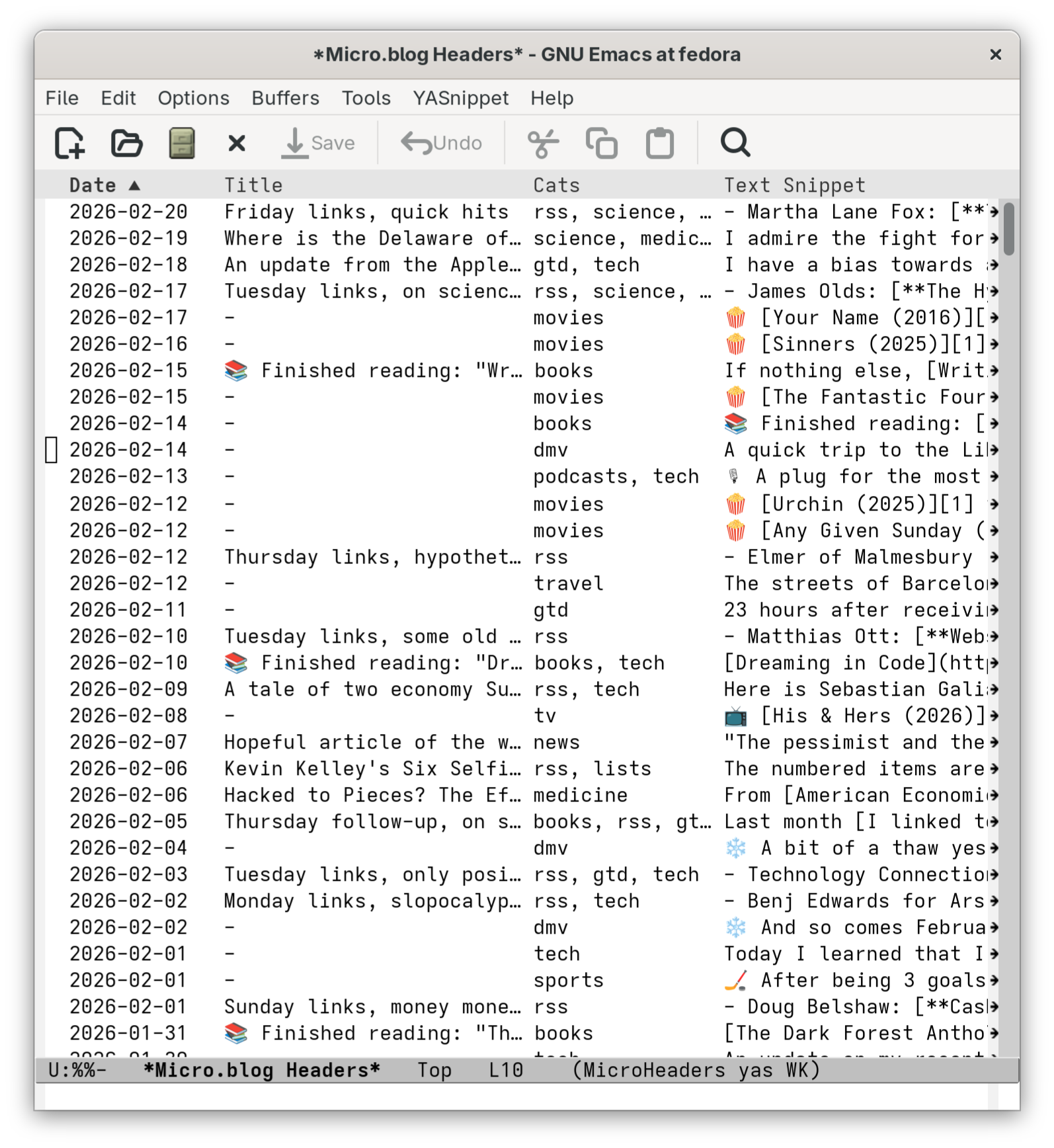

It took me less that two hours with Google Gemini to create microblog.el, a micro.blog manager for Emacs which can edit old posts, create new ones (even with images), auto-complete tags and perform lightning-fast full text search. What a time to be alive!

Notice that I have used the past tense about social media in much of this column. To my mind, it is dead, as I quit it long ago. That is a move to be recommended. (Don’t announce that you are leaving, though. Just leave. You are not Adele cancelling that last Vegas residency of hers.)

Indeed.

Part 2 of my Apple decoupling is not ready just yet, but I couldn’t wait to share this preview of my (and Google Gemini’s) micro.blog editing client. I am writing this in the browser as image attachment is not yet fully baked, but it can download and edit existing posts just fine.

Emacs FTW!

I admire the fight for clinical trial abundance, I truly do, but the longer I think about it the more convinced I am that making nips and tucks to federal law and FDA guidance is the wrong way to go about it.

I have been involved in clinical trials for more than a decade and have seen it through the eyes of an investigator, sponsor and IRB member directly, and owing to a few friendships with ex-FDA employees, from the eyes of regulators as well. The common thread between all cases of delay and all frustrated attempts to speed things up were not laws and regulations but humans. The blankfaces and boxcheckers. Those IRB members who prefer the list of possible toxicities in a consent form in table form as opposed to a list, or a list as opposed to a table, and with percentages of expected occurrences instead of qualitative statements of possibility, but can you please explain what does percentages mean in qualitative terms, and is it “toxicity” or “adverse event”, and you should list only true toxicities not hypotheticals, except when we require you to add each potential adverse event — sorry, toxicity — whether it happened in this or other trials or not, and for each round of these changes there is another 3-week turn of the IRB roulette during which a different person may view the edits and give their own two cents — leave their own fingerprint.

And that is only the IRB! Their are personal imprints to be made at every level of clinical trial desing and implementation, between different departments of the Sponsor, “key opinion leaders" Or “KOLs”. The whole KOL ecosystem is worth writing about at length, just not today. sitting on advisory boards, administrators and worriers-in-chief at clinical trial sites, and even, rarely, clinical trial investigators themselves although in the US at least they are the ones least involved in clinical trials. More often than note, the way to leave your fingerprint is by citing a rule or a law or precedent from the FDA or the IRB or some other state-level regulatory agency whether or not said rule, law and/or precendent apply.

To be clear: most people in the clinical trial ecosystem are not like this. But much like airport noise complaints, in which one household accounted for almost 80% of all complaints, it only takes a handful of people to gum up the works and make it appar like the whole system has conspired against smooth trial execution.

So ho do we achieve abundance? Cutting down on the laws that govern trials is an option, and would certainly reduce the degrees of freedom at which blankfaces and boxcheckers operate. But America is a country of min-maxers and I can easily see things going sour with drive-by trials and phase 1 clinics being run out of a storage unit in South Florida. Which operate even now, so just you wait for the walls to come down and the minmaxing trial beast to be unleashed. Chesterton’s fence and all that.

Could we not reduce the number of gummer-uppers in the chain instead? There are plenty of trials that are quick to start, quick to execute, and not even all that costly, largely due to people being reasonable. Can we inject more reasonable people into the ecosystem, if we can’t inject more reason into people who are already there?

This thought brought me to Delaware, the second smallest state of the USA that has 60% of Fortune 500 companies incorporated there owing to the convenience, flexibility and predictability of its corporate law system. To my layperson’s eyes it seems, from the example of Delaware, that its not the law itself that makes the difference but rather who implements it and how — which was on spectacular display earlier this week.

Convenience, flexibility, predictability.

Now clearly the Delaware of clinical trials can’t be Delaware — it is far too small and wouldn’t have enough trial candidates. But California, Texas, Florida and New York could all vie for the spot, each having a population similar to Australia, the phase 1/2 promised land. Texas was the first to make some waves, tiny and of an uncertain direction, but in the ballpark of what would be needed. The only changes that federal law needs are those that would allow the states to compete among themselves in being clinical trial champions.

If that last image made you think of China and its competing provinces, it is for a good reason: the Chinese have been eating everybody’s lunch for the past few years, in large part because of the vicious internal competition elaborated on elsewhere. There are other lessons there, for some other time.

I have a bias towards action, so when an idea forms with a clear path forward and little if any downside I tend to go for it. Now, the plan to detach from Apple will take years to fully implement, but stage 1 is well under way: to find and use workable Linux parallels to every app I’ve come to learn and love over the years. Some of those I have already replaced (goodbye, OmniFocus, hello, Emacs org-mode) and some are still a work in progress (you won’t believe what will end up replacing MarsEdit), but before all that here are a few things about replacing the OS.

I was worried that I would be lost between having to choose between various distributions of Linux, each with its own set of trade-offs, but having an M1 Macbook Air significantly limited my choices which in this case was a good thing. Asahi is a project to bring Linux to Apple Silicon chips and so far M1 and M2 series are almost fully supported. And Asahi chose Fedora as its flagship distrbution, so Fedora Asahi Remix was the obvious choice, though several other distribution since then have become available on Apple Silicon thanks to Asahi.

Still, there were two more choices to make: what desktop environment (KDE Plasma or GNOME), and how to actually run the thing (via Parallels or actual dual-booting). It seems like the Asahi people would want me to chose KDE — it was the default choice during setup and they highlight it on the Fedora Asahi page. Alas, it just looked to much like Windows and the configurability they touted as a feature also gave me pause: how much fiddling would I do as a procrastination mechanism? GNOME looked sort-of like MacOS but was clearly its own thing and dare I say was even more polished than Liquid Glass. So I picked GNOME.

As for the booting mechanism, Parallels or some other method of virtualization would 1) have been a cop-out, 2) still have me exposed to the disaster that is MacOS 26 Tahoe, and 3) not be representative of the actual experience once the M1 Air kicks the dust and I have to find a new laptop. So I dual booted. Fedora Asahi makes this incredibly easy, with a single incantation at the Terminal shrine:

curl https://alx.sh | sh

This downloads the entire thing, partitions the drive, installs the new OS via a MacOS Recovery drive (don’t ask me how this works, but it work it did) and changes the boot sequence to default to Linux. It would have been magic if not for the partitioning part, during which I found out that no I do not actually have 300+ Gb of free space on my 1 Tb SSD as MacOS doesn’t count the space used by temporary and cash files as occupied and would rather users don’t know about them at all.

Fortunately there is DaisyDisk which was one of my first Mac App Store purchases back in 2012, only the App Store version also doesn’t have access to these hidden files because why would people know what is on the hardware they paid for, so I had to re-purchase the app from the developer’s website. On one hand no harm no foul — I’ve had and use the software for more than a decade — but on the other this kind of shenanigans is exactly why I’m skipping Appletown.

So if I had to order how much time things took: partitioning was the longest and most tedious part owing completely to Apple’s opaqueness, writing this section comes after that, and the actual Fedora Asahi install was by far the quickest. The last time I dealt with Linux before this was when I installed Ubuntu Gutsy Gibbon back in 2008 to dual-boot with Windows XP or what not (I was never a Linux maximalist), and oh my how things have changed.

A few things you should know before you type the incantation in your own terminal: Thunderbolt is not supported so no chance of a second display unless you find a Linux-compatible dock; touch ID doesn’t work and I doubt that it ever will; sleep mode is not fully baked so if your workflow involved leaving the laptop on for days relying on power management magic you should be prepared to switch back to turning the thing off at the end of a work day, which hey may actually not be a bad thing if it makes you less tempted to just take a quick peek at the work email during a movie watching night bio break, right?

The first one was almost a deal-breaker for me since I have grown attached to the LG 5K Ultrafine display, but everything else brought enough relief — even joy — for me to stick to the program. Now, for the Linux apps that brought joy back into my laptop use you will need to come back later this week, as this post has already gotten longer than planned. So it goes when you’re having fun.

Why no scientist should hang their hat on a single pet theory, with real-world examples. The same problem haunts the world of biotech even as its denizens claim their superiority at drug development.

About a recent Nature Medicine article which found that LLMs were no better than Google at helping patients diagnose and manage their self-reported maladies. The reasons are those that I suggested two and a half years ago — ChatGPT can give you the correct answer from a properly structured clinical vignette, but the art and science of medicine are transferring the reality in front of you — the patient’s haphazard story, their hodge poge of medical records, the subtle physical exam findings — into something salient. Not saying AI won’t get there at some point, but it clearly still needs work.

Rao has collected 101 (!?) of his best Twitter threads and a few hundred single tweets into a book. A note on the title page says:

This book is LLM-friendly. Point your LLM to venkateshrao.com/twitter-book if you want it to explore it. A full interactive archive, explorable via an AI oracle, is under development.

Living up to his call to be (slightly) monstrous.

Yes, it is a person I hate making a good point, which is that the brutalist architecture of L’Enfant Plaza is out of place so close to the National Mall and should be kept where it belongs. I even prefer the proposed neoclassicist style to what Trump’s ego would want, which I imagine to be a Dubai And even Dubai would be better than what’s in the President’s id. on the Potomac.

Cabel Sasser: Wes Cook and The McDonald’s Mural. Sasser expands on his wonderful 2024 XOXO talk about a 10-year quest, which you should of course watch before reading.

Luke Bouma for Cord Cutters: Babylon 5 Is Now Free to Watch On YouTube. Could it be true? Would the badly run and technologically incompetent Warner Brod Discovery really commit this act of unprovoked altruism on the official Babylon 5 Youtube channel? Of course not — as of today the uploaded pilot is set as private.