Fairwell, Kindle

I As a side note: Paperwhite is objectively worse in turning pages than the original Kindle. Poor touchscreen and unclear areas mean that I am never quite sure what will happen when I try to turn the page. Having real clickety-click buttons — not that capacitive junk — would have greatly improved the experience. tried using my Kindle more, I really did, especially for nighttime reading for which Paperwhite’s backlight seemed tailor-made. But I couldn’t. The experience felt off, and no matter how good the book was, picking up the tablet and flipping through the pages felt like a chore.

Scrolling through micro.blog’s timeline, I think I found out why:

surveys indicate that screens and e-readers interfere with two other important aspects of navigating texts: serendipity and a sense of control. People report that they enjoy flipping to a previous section of a paper book when a sentence surfaces a memory of something they read earlier, for example, or quickly scanning ahead on a whim. People also like to have as much control over a text as possible—to highlight with chemical ink, easily write notes to themselves in the margins as well as deform the paper however they choose. The Reading Brain in the Digital Age

I don’t know about “chemical ink”, but knowing where I am in the book — especially a 700+ pager Content warning: A nazi biography. — is important for how I retain information (less important) and my sanity (slightly more so).

As for reading proper (chemical?) books at night: that problem may be solved by this one simple trick, not due to arrive until Thursday. Let’s see how it goes.

My Venkatesh Rao reading list

As obscure public intellectuals go, Rao is fairly well known online, but every day, somebody’s born who’s never seen The Flintstones, and the man does have a knack for packaging phenomena both permanent and ephemeral into digestible mental models which you can use again and again. Sure, you could check out his official New Reader guide — and there is some match between that and the list below — but doesn’t a bespoke list on an even more obscure personal blog make it more adventurous?

- The Gervais Principle, which should have been a book (and is much better than his only actual book). You will never look at office dynamics the same way again.

- The Cactus and the Weasel, the extension of the hedgehog and the fox dichotomy which made me fall in love with 2x2s, and also realize that I was a fox trying to fit in with a crowd of hedgehogs.

- The Premium Mediocre Life of Maya Millennial, wherein he coined the syntagm “premium mediocre” which perfectly captured the 2010s esthetics

- A Quick (Battle) Field Guide to the New Culture Wars, which made me want to spend as little time as possible on social networks in general, and one social network in particular, which is a good thing!

- The Internet of Beefs, which finally made sense of the ridiculous back-and-forths which were so common on

TwitterX. - Against Waldenponding, which earned him an invite to the best podcast out there, and which is also the reason I am writing this, having recently been reminded of Rao’s work.

Enjoy the multiple branching rabbit holes!

Finished reading: Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard 📚

Nuggets of brilliance floating in a slurry of overwrought prose that at times made it a slog to read. Still, remarkable. Any similarity to Walden is superficial, so check it out even if you, like me, abhor Waldenponding.

📚 Currently reading about sea life in Oceanarium, our 4-year-old’s favorite book. You can learn fun and interesting things this way.

For example, it is clear that peacock mantis shrimps are neither peacocks nor mantises, but did you know they weren’t even shrimps? They are, however, mantis shrimps. Not confusing at all!

Finished reading: The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka 📚

My wife was first to notice it was was not the type of book I usually read — which is to say fairly obscure 50-year-old works of non-fiction. This one is a brand novel that won the Booker prize last year, and I am not at all embarrassed to say that is was the prize that led me to it — M John Harrison of Light, and several other of my favorites being on the jury and deeming The Seven Moons… a worthy contender.

And you know what, it is! I absolutely see why Harrison, he of baroque prose and unintelligible place names on planets far, far away, chose the book, some parts of which are as inscrutable as the denser sections of Viriconium. Only, it’s not a fantasy world on another planet, it is 1980s Sri Lanka, and the things people do to each other are more horrifying than anything Harrison could have come up with for the mere fact of things like that actually having occurred, and the world not caring much, back then or now.

Ultimately, Karunatilaka pulled two great tricks, one tactical the other strategic. The tactical one was to write a novel in second-person singular that actually works. The strategic was to persuade the world that a fantasy murder mystery featuring ghosts, demons, ghouls, and a host of other supernatural and real-world monsters was not yet another piece of genre fiction. Feats worthy of a Booker prize, indeed.

The idea that the act of forgetting binds together both perpetrators and victims in the common pursuit of survival is at once deeply humanistic and at the same time deeply unsatisfying to moralists who prefer heroes who win out and villains who receive a timely come-uppance. But such endings made little sense to people in places such as Czechoslovakia, for whom learning to live with injustice and defeat was a geographical requirement.

And to the list he goes…

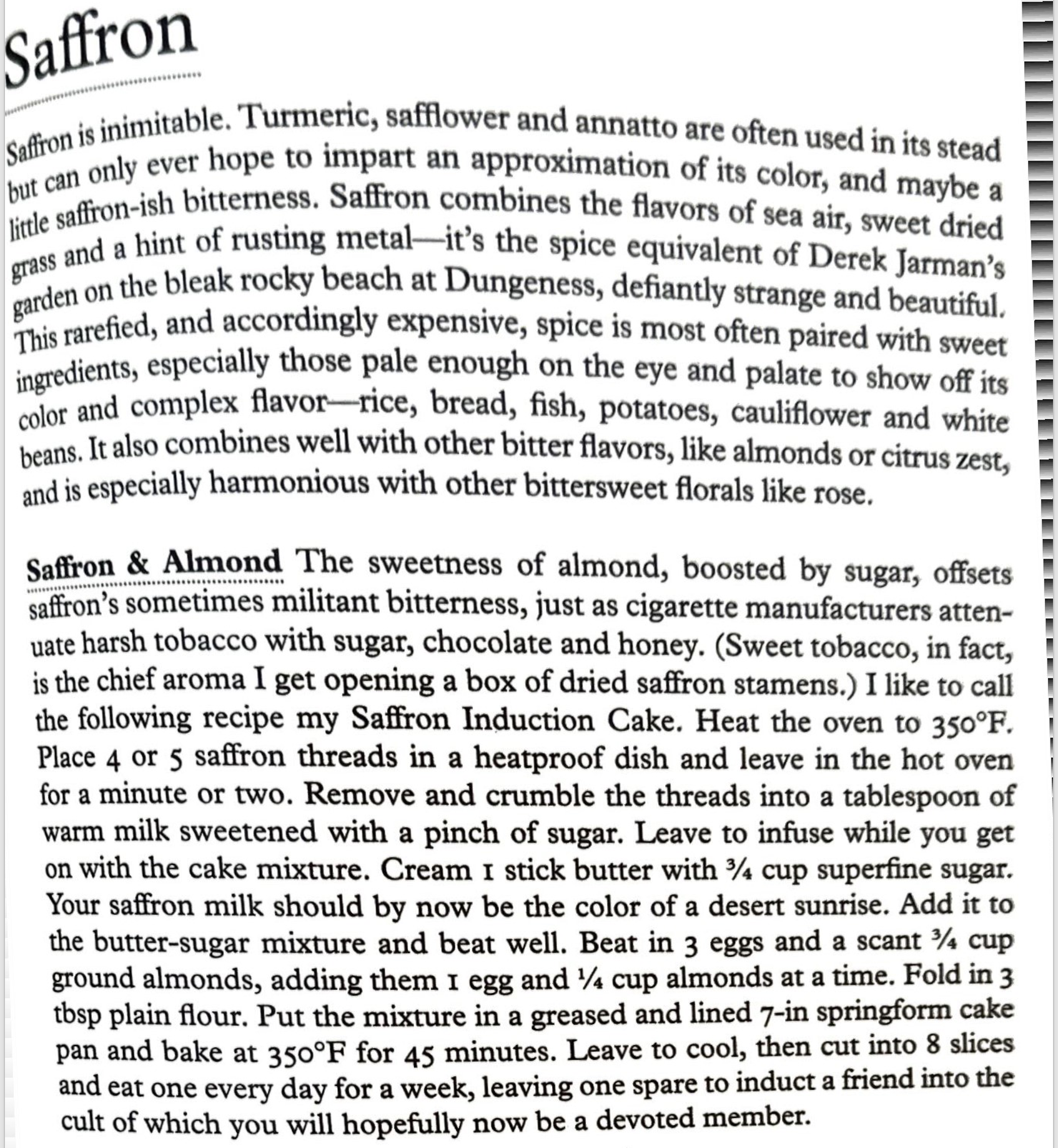

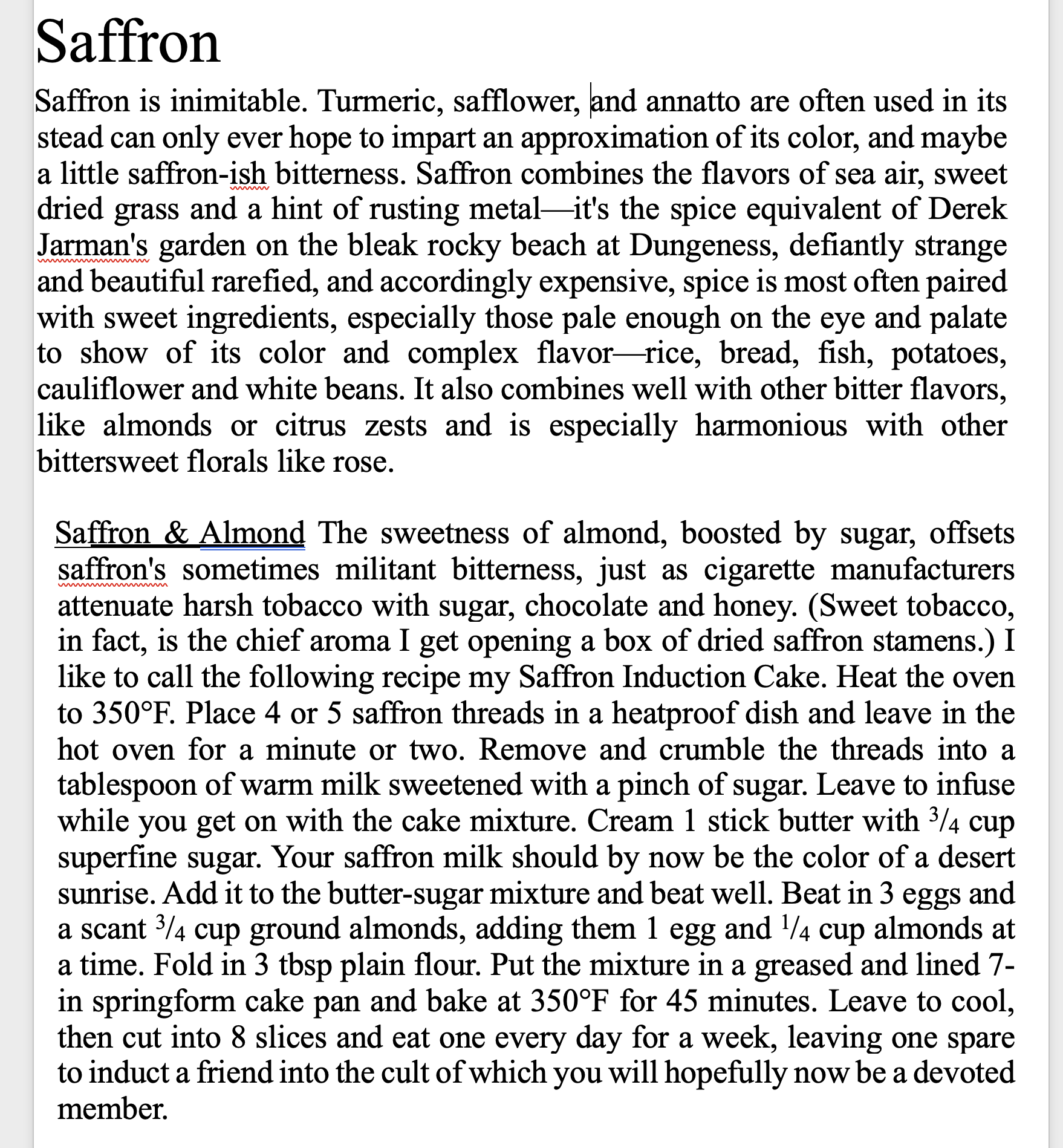

Microsoft is changing our household’s recipe game: no more bad photocopies or thick books on the counter when you can snap a photo and convert it to Word (and, when I have time, Markdown) in the Office365 app. This one is for a delicious saffron-almond cake, from The Flavor Thesaurus. ⏲️

Cool resource alert: Improving Your Statistical Inferences by Daniël Lakens has the best introduction to p values I’ve seen on the free web. Frank Harrel’s Biostatistics for Biomedical Research has been available for a while, but only suitable for advanced readers.

Finished reading: In Defense of Civilization by Michael RJ Bonner 📚

Michael Bonner is the anti-Harari: the history he writes about is narrower in scope and more precise, the present more grounded in reality, the future less bright — unless we work hard for it. He will not be speaking at Davos.

Finished reading: The Formula by Albert-László Barabási 📚

The perfect self-help book for your nerd scientist friend who wants to succeed in academia; broadly applicable to other areas of human endeavor, such as competitive hot-dog eating, crocheting, and investment banking.