Shark teeth

Visiting Montauk beach at Calvert Cliffs, a family member had one mission: to find a shark tooth. Millions of years ago, this part of Chesapeake was warmer and mostly under water. Many a shark dropped a tooth or a hundred during that time; today, they tend to drift to the shore with some regularity.

Searching for a speck of black in a tapestry of white-gray brought to mind Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, more specifically the chapter about learning to see, and yet even more specifically, her discovering praying mantis egg cases This is a longer blog post from The Examined Life about writers and insects; scroll down for the Pilgrim… excerpt. everywhere she looked, once she learned what one looks like.

My own learning-to-see training started with watching birds — not organized or consistent enough to be called birdwatching — and realizing in short order that not every brown-gray bird smaller than a robin is a sparrow, that blue jays, cardinals, and woodpeckers are actually quite abundant even in urban areas, and that those blue jays, as magnificent as they are, usually sound like nails on a chalkboard. The beach makes for even better training grounds. For novices like us there are mermaid’s purses and loggerhead turtle tracks — we saw both during our Outer Banks excursion — things alien enough to immediately be recognized as something. The mental exercise consists of discovering what that something is.

Not so with shark teeth, especially not with the small ones you are more likely to come across during a daytime summer stroll, as opposed to a planned break-of-dawn winter expedition. Is it a spiky piece of iron ore? A fossilized crab claw? Tooth of a mammal? Who knows!? Short of finding a 6-inch dental behemoth, casual beachgoers like us will come up with a million reasons why this black triangle isn’t an actual tooth, and why this other may be, without ever knowing if they are correct. Annie Dillard could put that insect egg casing in a jar and see dozens of tiny praying mantisses scuttle out and devour each other. I can put my black triangle in a dish and look at it until the Sun implodes, and it will continue being that same black triangle, possibly melted.

Unless, of course, we find an expert to tell us why these ridges here mean that it comes from a shark’s jaw, or why this dent over there means it is actually part of a crab. And, knowing that, we will know with certainty — conditional on us trusting the expert — what those two particular artifacts are, but could hardly extrapolate to other pieces of black material found on the beach, and most certainly not to those nestled on the forest floor, or buried in the desert sands, or hiding under the carpet of a 3-story walk-up.

This is in fact very much how medicine works: sometimes, the symptoms are clear enough and occur often enough that you may know as well as an MD that there is a urinary tract infection brewing. But too often — most of the time, in fact — the problems are subtle and chronic and may not develop into something recognizable until it is too late — in which case you better find an expert — or, maybe, never amount to much of anything — in which case you need that expert even more, the most valuable part of medical expertise consisting of the knowledge and experience needed to muster the confidence to say that something is just a piece of rock.

Update: Two months later, we went back and found some.

Of roasts and awards

I recently attended a residency graduation party at an academic medical center, for the first time since the pandemic. Two things struck me:

- So. Many. Awards. For the residents. For the faculty. For the ancillary staff. There were nearly as many awards as there were graduating residents.

- No roasting of the graduating house staff, or even a hint of humor of any kind. This used to be the highlight of any graduation party.

Award inflation is akin to grade inflation: they have become currency for further post-graduate training and, more importantly, faculty promotion. With the recent focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion, a whole new spectrum of accolades has opened up. So yes, there is a reason for all those plaques being thrown left and right, but it was funny nevertheless to see faculty speed through the list of graduates, then spend the next hour patting themselves on the back.

The lack of a proper roast was more concerning. Has the environment become so fraught that the residents are concerned about offending anyone? Humor is to dialogue what beavers are to a river: sometimes a nuisance, but also the hallmark of a healthy ecosystem. Or should I say good humor; when done lazily and as an afterthought, roasts too often devolved into a series of racial and sexual stereotypes. I imagine that is why some places have done away with them, which is also a lazy, unimaginative thing to do — you would think that with all the stress on DEI, the graduates would if anything be more capable of doing a character/personality rather than race/orientation-based roast.

What I hope DEI workshops did not teach them is that they should go out of their way to avoid making people uncomfortable. Sometimes people should be uncomfortable, and making them squirm just a little bit at the highest peak of their career-to-date is the best time for it. They will have the entire rest of the night to pat themselves on the back.

That feeling you get when something a long time coming finally does come out

I have always admired prolific writers like Matthew Yglesias and Scott Alexander — both now on Substack, and not by accident — for their ability to produce tens of thousands of words daily, My admiration being tampered somewhat by ChatGPT and other LLMs, which are about as intellectually and factually rigorous as Alexander, and slightly less so than Yglesias; some sacrifices do have to be made in the name of productivity. on top of the random bite-sized thoughts posted on social media. There are only so many words I can read and write in a day, and for the better part of the last year, my language IO has been preoccupied by helping clean, analyze, interpret, and write up the results of a single clinical trial, which are now finally out in The Lancet Neurology. Yes, my highest impact factor paper to date is in a neurology journal. Go figure.

The paper is about our clinical trial which used the body’s own immune system to treat autoimmune disease — and a particular one at that, myasthenia gravis — via technology that up until now has only been used against cancer (CAR T cells). It has made a decent impact since it came out less than two days ago. It got a write-up in The Economist, for one. Endpoints News as well. Evaluate Vantage got the best quote — it is at the very end of the article. And there is a whole bunch of press releases: from National Institutes of Health, University of North Carolina, Oregon Health and Sciences University, and of course Cartesian Therapeutics.

What went on yesterday reminded me that Twitter is not going anywhere any time soon: all of the above releases were to be found only there, not on a Mastodon instance, the journal’s own media metrics do not — and can not, at least not easily — trawl the Fediverse for hits, and I can’t just type in “Descartes–08”, “myasthenia gravis CAR-T”, or “Cartesian” into a Mastodon search box and get anything of relevance. One could, of course, argue that you wouldn’t get anything of relevance on Twitter either, most of the discussion consisting of people who have barely read the tweet, let alone the article. And one would be correct. And while most of the non-Web3/crypto tech world has moved out, it looks like people in most other fields, from medicine to biotechnology to the NBA commentariat, are maintaining substantial Twitter presence.

This will, of course, have no impact on my commitment to staying out of the conversation to the extent possible while maintaining a semi-regular schedule of 500-character posts, which may now, IO bandwidth having opened up, become a tiny bit longer. Thank you for reading!

WaPo: "Could cancer become a chronic, treatable disease? For many, it already is."

Washington Post’s Katherine Ellison on the striking decrease in mortality from lung and breast cancer in the US:

There are many and varied explanations for the progress, says Memorial Sloan Kettering oncologist Larry Norton, including “better early diagnosis, better imaging, better blood tests, better preventive measures and better treatments, including precision medicine with gene-profiling of patients’ tumors.”

The rest of the article focuses on treatments — immunotherapy in particular — And yes, of course dostarlimab was mentioned. Once a darling, always a darling. and cancer survivorship, but in discussing decreasing deaths from lung and breast cancer the article missed an opportunity for some education in cancer epidemiology.

The two sources chosen to present these data, ASCO’s cancer.net for lung and Breastcancer.org for breast are lacking in two ways: they are an impenetrable wall of text without much context, and they both have an agenda. Now, it happens that I agree with ASCO’s agenda — I am a dues-paying member — and don’t know enough Breastcancer.org to form an opinion, but neutral parties they are not. If only there was a tax-funded, publicly available database which could help us visualize trends in cancer statistics.

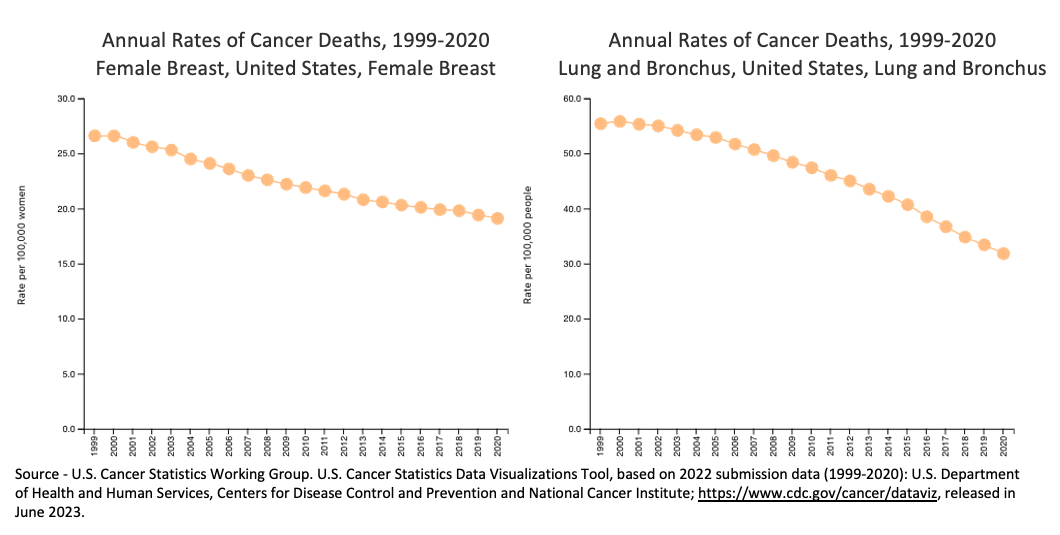

Now it so happens that the CDC maintains such a database, with its very on visualization tools, and it is exactly what we need. It will even make your PowerPoint slides for you! And yes, deaths from both lung and breast cancer have been steadily decreasing for the past two decades.

Lung and female breast cancer mortality in the United States, 1999–2020.

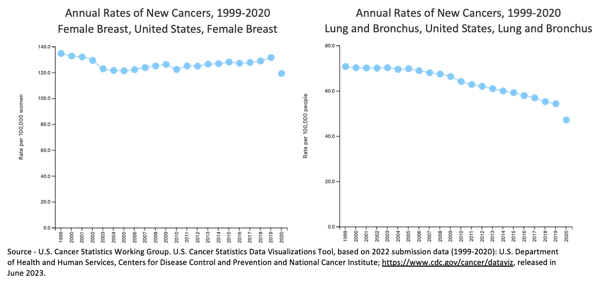

But is it because of better prevention, early diagnosis, more effective treatments, or all three? Looking at cancer incidence — the number of newly diagnosed cases per year — may help some. Better prevention would lead to decreased incidence, early detection would lead to an increase, a combination of the two may cancel each other out leading to a flat line, and any change in treatments would not affect it at all.

Lung and female breast cancer incidence in the United States, 1999–2020.

A slight initial dip in female breast cancer incidence followed by an even slighter increase make me think that early detection — all those mammograms — is superimposed on better prevention. The case is less ambiguous for lung cancer: the incidence is plummeting. In both cases, “prevention” was initiated by the 1964 Surgeon General’s report on tobacco smoke which led to massive anti-smoking campaigns from the 1970s onwards. The results weren’t immediately obvious — not having to air out all your clothes after a night out notwithstanding — but cancer rates started dropping after 20 years, and 50 years later we are reaping the full benefits.

Note that in lung cancer the mortality slope is steeper than the incidence slope. And while this may be explained by early detection and better treatments, it is possible that at least some of the improvement over newly diagnosed lung cancers is due to non-smoking associated lung cancer being generally less aggressive and occurring in younger and healthier people than tobacco-associated cancers. What could help unravel these different components — and highlight the increasing importance of cancer survivor healthcare — would be a prevalence curve: how many people in the United States are currently living with a particular cancer. Alas, those data are not available.

If you thought interpreting those four curves was interesting, do go back to the CDC database and check out the incidence and mortality curves for thyroid cancer — that poster child of over-diagnosis — and prostate cancer, the incidence of which fluctuates ever which way with changing screening recommendations but with mortality marching downwards for the last 20 years.

After seeing a friend and collaborator yet again plant foot firmly in mouth, I begin to see a pattern. A course on ergodicity should be a requirement for a public health degree, since the masters of public health keep getting it wrong (see also: the screening colonoscopy debate).

Back to school

It will be 13 years this June since I have left a job teaching histology at the University of Belgrade to start internal medicine residency in Baltimore. And lo and behold, I am back teaching, sort of.

UMBC — University of Maryland Baltimore County to friends — is starting a graduate course on clinical trials. I will be helping out Wilson Bryan, the recently retired Director of FDA’s OTAT (aka “head of cell and gene therapy”), to design and run it. Maybe even do a lecture or two. The two of us talked briefly about the new course on a UMBC podcast, This is also where I learned what my title would be. Graduate instructor, apparently. The amount of paperwork required was not commensurate with the title. Oh my, all that docusigning… which is out today.

The course will be an in-person/on-line hybrid, so even those not in the area — and it will be held at UMBC’s Shady Grove campus — may join this coming September. From what I understand, giving people who are not physicians the opportunity to learn about designing, running, and interpreting clinical trials is a rarity, so it will be interesting to see who shows up and where the discussion leads us.

So, 13 years… Different university, different subject matter, but how much could things have changed since then anyway?

As two of our three offspring lay in bed with fevers, a thought comes to mind: could covid have caused this never-ending chain of infections which began last fall, during which a week rarely goes by in which no one misses at least one day of school because of illness? Has it destroyed our immune systems, made us more susceptible to other infectious diseases? There is, after all, no end to articles in press both professional and lay which warn of long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 on various lymphocyte subsets.

Well, no. Or at least highly unlikely. A 5-person household with three school-aged children will have one respiratory virus or another circulate a full two thirds of the year. With our youngest starting PK3 last fall, we have become that household, and 65% sounds about right.

Woe to us and anyone who visits our little Petri dish.

And in some positive news — can you imagine those still exist? — the US Food and Drug Agency has issued their draft guidance on decentralized trials (PDF download). America is playing catch-up with the UK in this regard, but better late than never!

May lectures of note

Exploring the link between Sickle Cell, α-Thalassemia, P Falciparum Malaria and Burkitt Lymphoma in Africa

- Speakers: Sam Mbulaiteye, MBChB, M.Phil., M.Med.; Swee Lay Thein, B.S., F.R.C.P., F.R.C.Path., D.Sc., FMedSci

- Wednesday, May 10 2023, 12pm EDT

- Watch here

Diabetes Mellitus: Great Progress; Diabetes: The Marathon of Life

- Speakers: Douglas Melton, PhD; Courtney Duckworth, MD

- Tuesday, May 16 2023, 4pm EDT

- Watch here

Is Cerebrovascular Disease Ever Really Silent? Stroke, Small Vessel Disease, and Cognition

- Speaker: Rebecca F. Gottesman, MD PhD

- Wednesday, May 31, 2023 12pm EDT

- Watch here

April lectures of note

The first good one is tomorrow!

Demystifying Medicine - How is the Brain Organized and How Does it Work?

- Speakers: Nelson Spruston, PhD, Janelia HHMI and Marcus Raichle, MD, Washington University

- Tuesday, April 4, 2023, 4:00:00 PM EDT

- Watch here

Ethics Grand Rounds: Is it Ethical to Appeal to Research Participants’ Altruism?

- Presenter: Beth Kozel MD, PhD Lasker Clinical Research Scholar, NHLBI Discussant: Alex Voorhoeve PhD Head, Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method, London School of Economics

- Wednesday, April 5, 2023, 12:00:00 PM EDT

- Watch here

Clinical Center Grand Rounds: From Bench to Bedside: A Translational Approach to Innovation in Research and Treatment of Perinatal Depression

- Speaker: Samantha Meltzer-Brody, MD, MPH, UNC Center for Women’s Mood Disorders, Department of Psychiatry University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Wednesday, April 12, 2023, 12:00:00 PM EDT

- Watch here

Demystifying Medicine - Fat: Biology and Staying Thin

- Speakers: Aaron Cypess, MD, PhD, NIDDK, NIH and Kevin Hall, PhD, NIDDK, NIH

- Tuesday, April 18, 2023, 4:00:00 PM EDT

- Watch here