🏀 Here is for another abysmal season!

A prediction, based on nothing but this short post from John Gruber and a hunch: within 5 years, Apple will have a deal to stream all college football. NFL may be out of reach, but for many people — Tim Cook included — NCAA is what matters.

As a not-so-recent graduate of a medical fellowship program, I often get spammy job offers via email, text, LinkedIn messages, etc, some of them with promises of eye-popping income. A memorable add mentioned over $800,000 annual compensation for a position in Caribou, Maine. It was telling that I was getting it for at least a year before it stopped, and if you were the brave soul who took up the job then please get in touch, I would like to hear how it’s been!

Often, the number is not mentioned at all. Those jobs have a clear advantage in terms of the institution, geographic location and time commitment. All others fall into two categories: “up to” and “guaranteed”. A decade-plus of reading Nassim Taleb’s writing has taught me to avoid the up-to and value the guaranteed.

Many people focus on “benefiting from disorder”, but this is in fact the basic asymmetry behind Antifragile, which Taleb touched on even earlier in his books. Cap the losses and yes, stay open for high — ideally unlimited — upside, but avoiding ruin takes precedence.

The up-to/at-least dichotomy is broader than job postings. “Up-to” precedes many numbers and sometimes, fair enough, it is important to mention and valid in the conversation. But sometimes — often? — it is uttered under the breath and while clearing throat to yell out a large number that is meant to impress, change minds, open up hearts… and wallets.

“You could earn up to $900,000 per year”, if you see 40 patients per day five days a week with 10 days off for the entire year. Extrapolate to other areas of life as need.

Drywalls weren’t a thing when I was growing up in Serbia and I don’t think they are used even now. I avoided putting up shelves as the whole stud-finding procedure was a bit of a dark art that could go very wrong in my inattentive hands, never mind that the placement was just too constraining — I didn’t want the placement of a towel rod to be decided by a home builder from 30 years ago. Then I discovered toggle bolts (also known as butterfly anchors), and I have been putting up shelves, hooks, screen mounts and other bits of hardware with wild abandon.

Now, using toggle bolts will leave behind a comically large holes if you ever change your mind about wall placement. This hasn’t happened to me yet, but when it does I will know to go to YouTube, which has become a living encyclopedia of crafts. Just in the last two months it has helped me with replacing a microwave circuit board and fixing a pair of broken shades, and I am no handyman. This is why I would never lump in YouTube together with TikTok, Instagram and other soul-sucking services, though it is always good to turn off the recommendations.

My third bit of advice is also wall-related: for anything you wanted to hang that’s too light to warrant a toggle bolt, use 3M’s Command strips. Yes they are just a tiny bit wasteful since you can’t reuse the one that’s stuck on a wall, but unlike nails or pieces of colored sticky rubber, they will not leave any trace once removed. They are a renter’s best friend.

And if you are renting, do not be afraid to change things around if you are in a managed property and don’t have the owner acting as landlord. Each time I moved out they person doing the walk-through was surprised by how unchanged everything was, and each time I thought to myself that I should have hung up that towel rod, or anchored that Kallax shelf to the wall.

When moving, the ideal is to hire someone to do everything for you, from packing to load to driving and the unloading. If you don’t have the means for it (and I haven’t), at least hire someone for the loading/unloading part, preferably someone with experience. Either way, if you pack yourself, packing everything save for large pieces of furniture into boxes — there should be nothing irregularly shaped that’s not in a box. And yes, I truly mean everything, even (especially!) the groceries.

So whenever you come by a trinket and wonder to yourself whether you should get it, for yourself or as a present for your children or significant other, picture yourself coming across it while packing for another move and try to imagine how would you feel: glad that you got to keep the memento, or resentful that it became just another piece of detritus that you have to stuff in a box.

Always on the lookout for new blogs, I was happy to see a former leader at the National Science Foundation, Jim Olson, start one (↬Tyler Cowen). Based on the formal and didactic style I would say I was not the target audience for it, but it is better then nothing. It may also provide a convenient catalyst for my own thoughts.

For example: Olson’s most recent post is about the replication crisis. He points the finger on verification not being sexy enough for grant funders and academic journals, which is true. But if anything, having more people verify more and more claims in the ever-growing steaming pile of academese would make things seemingly worse, at least in the short term. This is the same kind of thinking that wanted to end medical reversals. You don’t want to end them, you want to make them unnecessary in the first place!

Now, fear of your claim being verified may frighten some researches from shooting from their hip, but unless paired with some sort of immediate punishment it would hardly make for a good stick. And what is preventing the person who made the original claim from demanding verification of the verifiers, and so on, and so forth, ad infinitum?

Olson also recommends more detailed methods, so that replication would be possible in the first place. This has already been implemented as anyone who had to fill out Cell’s never-ending STAR Methods can attest. Nature and Science have similar requirements, and some of them don’t even have a word count limit for the Methods section. Granted, many other journals aren’t as rigorous, but that should help you figure out which journals to follow.

So, instead of asking why we don’t have more people verifying claims, I would ask why we needed verification in the first place. Olson touches upon the core issue, mentioning “the time horizon problem”:

NSF grants run 3-5 years. Tenure clocks run 6-7 years. But scientific truth emerges over decades. We’re optimizing for the wrong timescale.

During my time at NSF, I saw brilliant researchers make pragmatic choices: publish something surprising now (even if it might not hold up) rather than spend two years carefully verifying it. That’s not a moral failing—it’s responding rationally to the incentives we created.

Of course it is about incentives. No amount of verifying will change that. People are chasing after tenure and accolades, not truth, and many a tenured professors shrugged their shoulders at the mansions of straw they had built over the decades. At best, they provided an easy target for a successor in the field to refute, unless of course there is a whole cabal of like-minded researchers protecting the dubious claims. But the default position is that these mansions of straw stay there, moulding and festering, side-tracking post-docs and spamming PubMed searches.

I have no clue what the solution may be. Maybe there is none and this is the equilibrium — let reality provide the final vote. But the status quo feels far from optimal.

If I had to name people who have influenced my life the most — not counting parents, teachers and other usual suspects whose very job is to influence you — the most surprising person on the list would probably be Mike Judge, the creator of Beavis and Butt-Head, Office Space, etc. Now, I was too young for Beavis and Butt-Head, never really got into King of the Hill and even though I appreciated the humor of Office Space I was merficuflly never exposed to that kind of office culture. No, Judge’s influence stems from a single movie, and in fact it was only the first five minutes of that movie that made a difference. I am of course talking about the introduction to Idiocracy (2006), in which a crude thought experiment pitted a WASP-ish couple of intellectuals against three trailers worth of rednecks and wondered which would result in more progeny.

No, the hereditary case for intelligence doesn’t make much sense, and the intro’s reliance on the pseudoscientific concept of IQ now seems quaint. But the fate of the two WASPs, ever waiting for better times to have children — or, more likely, the one-and-done — until it was far too late, this rang true. It was a good warning for someone just about to graduate from medical school (2008) and start what can be a never-ending journey of post-graduate medical education in the US (2010–2017).

More importantly, my then-medical student colleague, now-wife saw the same movie and had the same thoughts. If all goes well — and this late in the game, it better — we will welcome our fourth child into the world next month.

It is therefore with great interest that I read Scott Sumner’s most recent article which for once had a good and descriptive headline: Billionaire baby boom. And he has some interesting observations:

Fertility rates seem to follow a sort of U-shape. People in central Africa are too poor to afford very many luxuries, so children become the focus of their lives. Upper middle-class professionals have enough wealth to provide themselves with all sorts of fun activities, but not enough to provide full time caregivers for their children. Billionaires have so much money that they can farm out the difficult parts of raising children to servants, and just do the fun stuff like playing with their kids.

Note that it goes without saying that the upper middle-class professionals would want to outsource care for their children, and pay for it handsomely. Also left unspoken is the secret wish of every upper middle-class parent for their children to go to an elite university, which means a certain high school, and middle school, and… no wonder you would want to stick to just the one.

Thankfully, Nassim Taleb’s Incerto innoculated me against that kind of thinking, and frequent exposure to products of the above system acts as a booster of sorts. Limiting how many children you have so that you could raise one certified IYI would be a very IYI thing to do.

Living in DC, we are very much the outliers in any social circle you can imagine. “You must be really disappointed” is what a (single child) friend said to our 13-year-old. And everyone assumes the baby was a complete surprise (it wasn’t). We do hear a lot of “I don’t have children so that I can have a glass of wine in a restaurant at 6pm”. That’s fine. From my experience in health care those kinds of lives tend not to be as fullfilled in old age, but that could just be selection bias.

Anyway, you can definitely have more than one or two children without being a billionaire, and have a reasonably good lifestyle at that. In fact, better lifestyle than anyone ever in the history of humanity including royalty, other than in the last ~100 years. Factor that in when you make your own decisions.

🏀 Here is for another abysmal season!

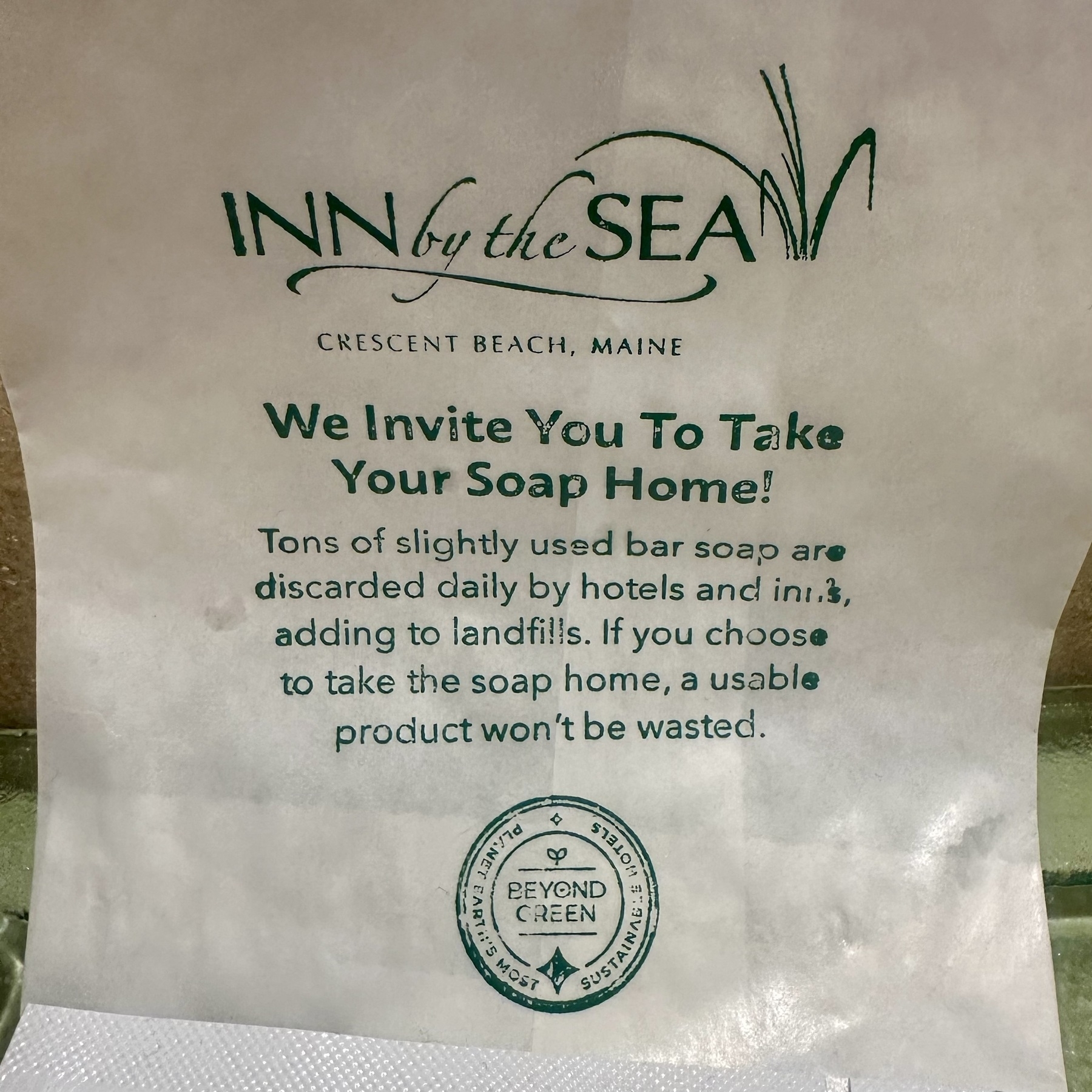

Most hotels have introduced a bunch of cost-cutting measures under the guise of “saving the environment”, but this is something I can get behind. Even the tiniest leftovers are good for making your own liquid soap.