❄️ A bit of a thaw yesterday, and various artifacts of bygone eras encased in ice for decades begin to emerge.

From American Economic Journal: Economic Policy about the effects of ransomware on patients: ↬Tyler Cowen

Ransomware attacks decrease hospital volume by 17–24 percent during the initial attack week, with recovery occurring within 3 weeks. Among patients already admitted to the hospital when a ransomware attack begins, in-hospital mortality increases by 34–38 percent.

The implication is that the computer systems being down has a huge detrimental effect on patient outcomes. What the abstract doesn’t get into — and I don’t have access to the full article — is how they calculated the in-hospital mortality among the already admitted patients. Many of them will have been discharged early or transferred to other hospitals if stable enough, decreasing the denominator and overestimating mortality. At least I hope that’s the case!

The numbered items are from Kelley’s recent post, comments below are mine after a bit more than a decade of experience.

Provided you have values to disseminate, know what they are, and especially know the difference between values and opinions because while your values may be identical your opinions will often clash.

Absolutely true. My wife and I have a running list of every brilliantly stupid and stupidly brilliant thing our progeny has said. It is long and growing ever longer.

Experiencing this right now while having both an infant and a teenager at home. You tend to forget how large that gap actually is since you cross it in daily — nay, hourly — increments, but it is complete helplessness on one end and taking the metro from school by yourself and going on a field trip to China on the other.

For being loved alone you could also get a pet, but there is also a need to love that — and please fellow cat lovers do not kill me for writing this — no pet can completely fulfill.

Well put. Though of course you also take a piece of your heart and put it into someone else, and then things may happen to them or they may be the thing that happens to other people, with strong feelings either way.

Amen.

Last month I linked to two things that are now worth following up on:

And on the abandoning Apple front:

❄️ A bit of a thaw yesterday, and various artifacts of bygone eras encased in ice for decades begin to emerge.

OK, these two are included more for saliency than positivity, but they are also good!

Update: Adam Mastroianni’s latest post fits here like a glove.

❄️ And so comes February, the worst month of the year for those of us in the northern hemisphere. This one will be particularly horrendous for residents of DC and the surrounding suburbs as we deal with snowcrete — DCPS schools are still on a 2-hour delay, but hey at least they’re open!

…doesn’t spend time worrying whether the entertainment industry should work the way it does. She describes how it actually works and moves forward accordingly. “I love money,” she says simply, without apology or shame. This is pragmatism: the view that some approaches succeed and others fail, so you’d better figure out which ones work and act accordingly.

See what makes money and do it! A plan so fool-proof it is a true mystery why everyone isn’t a billionaire.

Pretty much nobody worships billionaires as a class. Most people worship at least one billionaire; that’s THEIR billionaire. Think old school paganism. Pantheon of gods, but a tribe will focus on one. A lot of immigrant Chinese Americans worship Elon Musk. Maybe it’s Donald Trump, or Kanye West, or Beyonce, or Taylor Swift, or Charlie Munger, or Warren Buffet, or Steve Jobs, etc.

Spot on! Somewhat surprisingly, Gelman’s never heard of Charlie Munger but if I had to pick a billionaire to “worship” (not that I would ever do such a thing), he could be the one. Certainly not Stevehole Jobs, and certainly not Munger’s partner Warren B.

One billionaire scratches another’s back; hilarity ensues. The story is outlined further in the NYT, but John Gruber has the correct headline. I hope Mrs. Trump will be able to brush off the harsh reviews and use her $28M direct payment from Amazon to finally gain the much-needed financial independence to which every American woman aspires.

This is the meat of the issue, and kudos to Moriarty for putting it so bluntly. Each billionaire’s billions were built on the backs of real people doing real work while missing family events, growing stomach ulcers and ultimately dying of cancer. If you think this is an exaggeration, do read a few accounts of what happens in even supposedly “good” multinationals. Well-meaning and good-hearted minnows never grow large enough to have to hide their money in Ireland. Financialization squeezed out their blood, sweat and tears and concentrated them into a handful of people who were clearly not well. Mirroring what happens to companies, those who have a firm grasp of morality and a sense of self never get to the first billion. In that light, I don’t think relying on the billionaire class to “fix” anything — or even to correctly identify the problem — is a sensible idea, so it is a good thing indeed that the country celebrating its 250th birthday this year has a track record of putting them in their place.

🏒 After being 3 goals behind, the Capitals win with an overtime tie-breaker from Sourdiff. The last time we were there he had a hat trick. Glad do witness both of his big days.

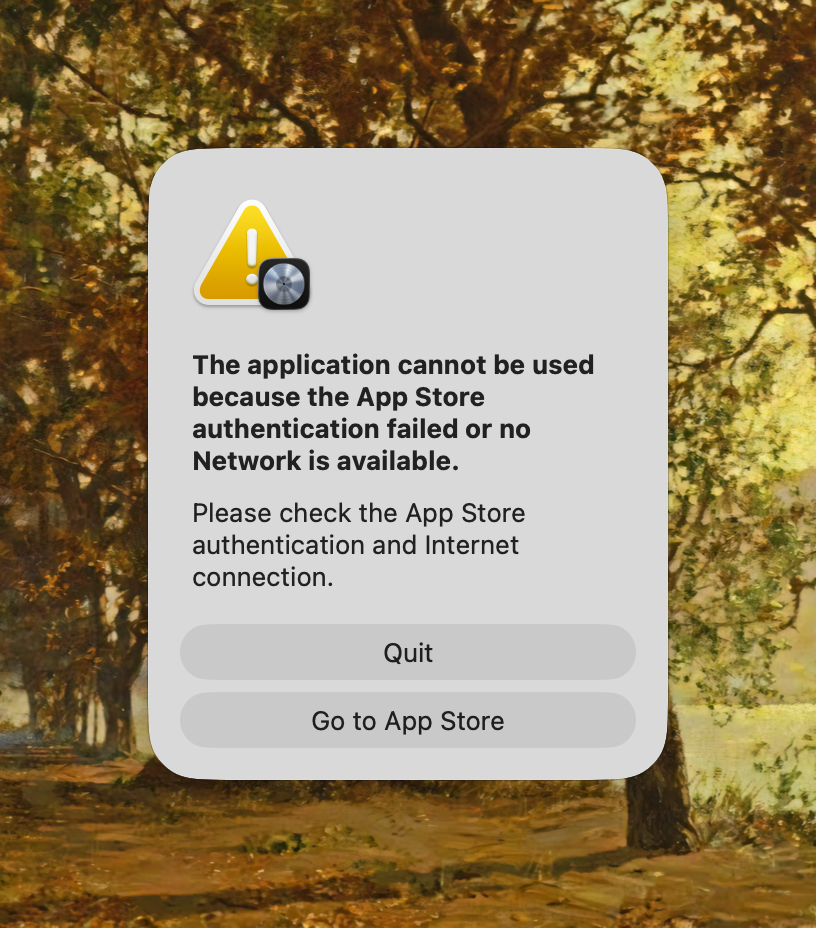

Today I learned that I paid $200 for audio editing software I can only use while online, which is tough to do when 37,000 feet up in the air. I don’t think this was an issue prior to the latest round of enshittification.