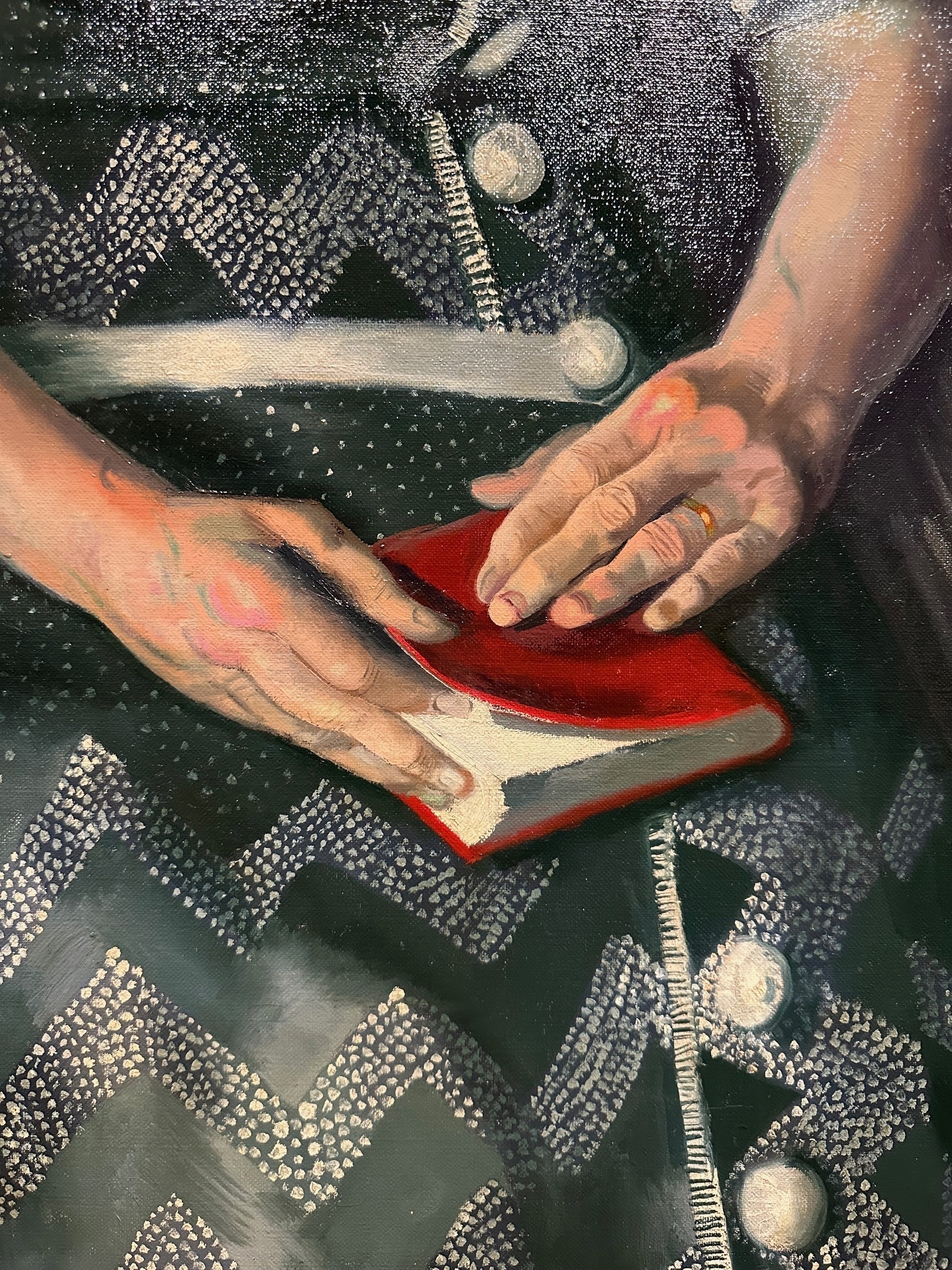

Here are Mr. and Mrs. Phillip Wase, as seen at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The odd and disengaged looks they both have aside, does Mrs. Wase look like she has a medical condition? Here is a hint.

This looks like textbook swan neck deformity, so Mrs. Wase probably had rheumatoid arthritis.

Tim Harford on the UK’s crumbling health care system:

In the case of St Mary’s Hospital in London, these weak foundations are all too literal. The Financial Times recently reported that the hospital had rotting floor joists, frequent flooding, a hole in one lavatory floor that led to a car park, a ward closed due to a collapsed ceiling, and sewage backing up out of the drains and into the outpatient department. Yet St Mary’s is no longer regarded as an urgent priority for investment, because five other hospitals appear to be in more imminent danger of falling down.

15-some years ago, when I was contemplating what to do after graduating from medical school, the UK was on the list of places for potential residency. It quickly got crossed off because it was hostile to foreign doctors — especially compared to the US — but good for me that it was!

December lectures of note

Not too much this month, for understandable reasons:

- Novel Insights Into Heart Brain Interactions and Neurobiological Resilience by Dr. Ahmed Tawakol; Wednesday, December 6 at 12pm EST.

- A Broken System: American Health Care Needs Combination Therapy by Dr. Martin Shapiro; Thursday, December 7 at 2:30pm EST.

- Investigating Stem Cells as Quantum Sensors by Dr. Wendy Beane; Monday, December 11 at 12pm EST.

- Harnessing Technology and Social Media to Address Alcohol Misuse in Adolescents and Emerging Adults by Drs. Maureen Walton and Mai-Ly Steers; Wednesday, December 13 at 12pm EST.

It gives me no pleasure to delete a feed that I have been following off and on for more than a decade now, but the logorrhea combined with intentional scandal-seeking behavior has become too much. Screen after awful screen of gotchas and callouts in a single post. Whatever for?

Quote of the morning:

My view is that any theory of what is wrong with American health care is true because American health care is wrong in every possible way.

Very true! This is from Alex Tabarrok’s review of what seems to be quite a misguided book about America’s handling of covid. I’ll take Tyler’s side of that debate.

There is both a science and an art to medicine. The “art” part usually comes into play when we talk about bedside manner and the doctor-patient relationship, but recognizing and naming diseases — diagnosis — is also up there. José Luis Ricón wrote recently about a fairly discrete entity, Alzheimer’s disease, and how several different paths may lead to a similar phenotype. This is true for most diseases.

But take something like “cytokine release syndrome”, or “HLH”, or any other syndromic disease that is more of a suitcase phrase than anything, and that can present as a spectrum of symptoms. Different paths to different phenotypes, with only a sleigh of molecular storytelling to tie them together. Yet somehow it (mostly) works. It’s quite an art.

Why not use machine learning to rank residency applicants?

I just finished attending a 1-hour career panel for UMBC undergrads thinking about medical school, and the one thing anyone interested in practicing medicine in America should know is that you really, really, really need to know how to answer multiple choice questions. It doesn’t matter how smart, knowledgable, or hard-working you are: if you don’t have the skills needed to pick the one correct answer out of the four to six usually given, be ready to take a hit on how, where, and whether at all you can practice medicine in the US.

To be clear, this is a condemnation of the current system! Yes, there are always tradeoffs: oral exams so prevalent in my own medical school in Serbia weight against the socially awkward and those who second-guessed themselves. But the MCQs are so pervasive in every aspect of evaluating doctors-to-be (and practicing physicians!) that you have to wonder about all the ways seen and unseen in which Goodhart’s law is affecting healthcare.

What would the ideal evaluation of medical students look like? It wouldn’t rely on a single method, for one. Or, to be more precise, it wouldn’t make a single method the only one that mattered. Whether it’s the MCAT to get into medical school, USMLE to get into residency and fellowship, or board exams to get and maintain certification, it is always the same method for the majority of (sub)specialties. Different organizations, at different levels of medical education, zeroing in on the same method could indeed mean that the method is really good — see: carcinisation — To save you a click: it is “a form of convergent evolution in which non-crab crustaceans evolve a crab-like body plan”, as per Wikipedia. In other words, the crab-like body plan is so good that it evolved at least five different times. but then if it is so great to be shaped like a crab, where are our crab-like overlords?

Being a crab is a great solution for a beach-dwelling predatory crustacean with no great ambitions, and MCQs are a great solution to quickly triage the abysmal from everyone else when you are pressed for resources and time. But, both could also be signs of giving up on life, like how moving to your parents' basement is the convergence point for many different kinds of failed ambition.

Behind the overuse of MCQs is the urge to rank. Which, mind you, is not why tests like USMLE were created. They were, much like the IQ tests, meant to triage the low-performing students from the others. But the tests spits out a number, and since a higher number is by definition, well, higher than the lower ones, the ranking began, and with it the Goodhartization of medical education. The ranking became especially useful as every step of the process became more competitive and the programs started getting drowned in thousands of applications, all with different kinds of transcripts, personal statements, and letters of recommendation. The golden thread tying them all together, the one component to rule them all, was the number they all shared — the USMLE score.

But then the programs started competing for the same limited pool of good test-takers, neglecting the particulars of why a lower-scoring candidate may actually be a better match for their program. Bad experience all around, unlike you are good at taking tests, in which case good for you, but also look up bear favor. On the other hand, there is all this other information — words, not numbers — that gets misused or ignored. If only there was a way for medical schools and residency programs to analyze the applications of students/residents that they found successful by whatever metric and make a tailor-made prediction engine.

Which is kind of like what machine learning is, and it was such a logical thing to do that of course people tried it, several times, with mixed success. It was encouraging to see that two of these three papers were published in Academic Medicine, which is AAMCs own journal. One can only hope that this will lead to a multitude of different methods of analysis, a thousand flowers blooming, etc. The alternative — one algorithm to rule them all — could be as bad as USMLE.

The caveat is that Americans are litigious. Algorithmic hiring has already raised some alarm, so I can readily imagine the first lawsuit from an unmatched but well-moneyed candidate complaining about no human laying their eyes on the application. But if that’s the worst thing that could happen, it’s well-worth trying.

No one is hiding the miracle cures

So, who wants to dismantle the FDA, you ask? Some patient advocacy groups, among others, aided by a few senators:

We need the FDA to be more insulated from these forces. Instead, every few years, legislators offer bills that amount to death by a thousand cuts for the agency. The latest is the Promising Pathways Act, which offers “conditional approval” of new drugs, without even the need for the preliminary evidence that accelerated approval requires (i.e., some indication that biomarkers associated with real outcomes like disease progression or survival are moving in the right direction in early drug studies).

…

This bill is being pushed by powerful patient groups and has the support of Democratic senators like Kristin Gillibrand and Raphael Warnock, who should know better.

The bill would codify using “real-world data” and unvalidated surrogate endpoints for something called “provisional approval”, a level below the already tenuous accelerated approval.

I can see how it may appeal to patients: you may get a promising new drug for your life-threatening, debilitating disease sooner via this pathway. On the other hand, there are already mechanisms in place that enable access to these: a clinical trial, for one. Or expanded access (a.k.a. “compassionate use”) for those who may not be eligible for a trial.

So how would “provisional approval” help? If anything, wouldn’t it transfer the risks and — importantly — costs of drug development from the drug manufacturer/sponsor/study investigator to the patient?

Ultimately, the reason why there aren’t many cures for rare, terminal diseases is not because the big bad FDA is keeping the already developed drugs away from patients but rather because they are devilishly difficult to develop at our current level of technology. Wouldn’t it then make more sense to work on advancing the technology The careful reader will note that the opposite is being done, and I write this as no great fan of AI. that would lead to those new cures? I worry that the Promising Pathways Act would solve a problem that doesn’t exist by adding to the already skyrocketing costs of American health care. But that could be just me.

(↬Derek Lowe)

Do you know about a horse named Jim? The one whose tetanus-contaminated serum was used to make diphtheria antitoxin that killed kids:

These failures in oversight led to the distribution of antitoxin that caused the death of 12 more children, which were highly publicized by newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer as part of his general opposition to the practice of vaccination.

There is a straight line from Jim to the creation of US FDA, in case you want to remove that particular Chesterton’s fence.

Seth Godin on the amateur presenter:

If you’re called on to give a talk or presentation, the biggest trap to avoid is the most common: Decide that you need to be just like a professional presenter, but not quite as good. Being a 7 out of 10 at professional presenting is a mistake. Better to stay home and send a memo.

This is exactly what happened last month at that medical conference. Colleagues, please stop.